They are not to be sold or reproduced for any commercial purpose, or used on any other web site.

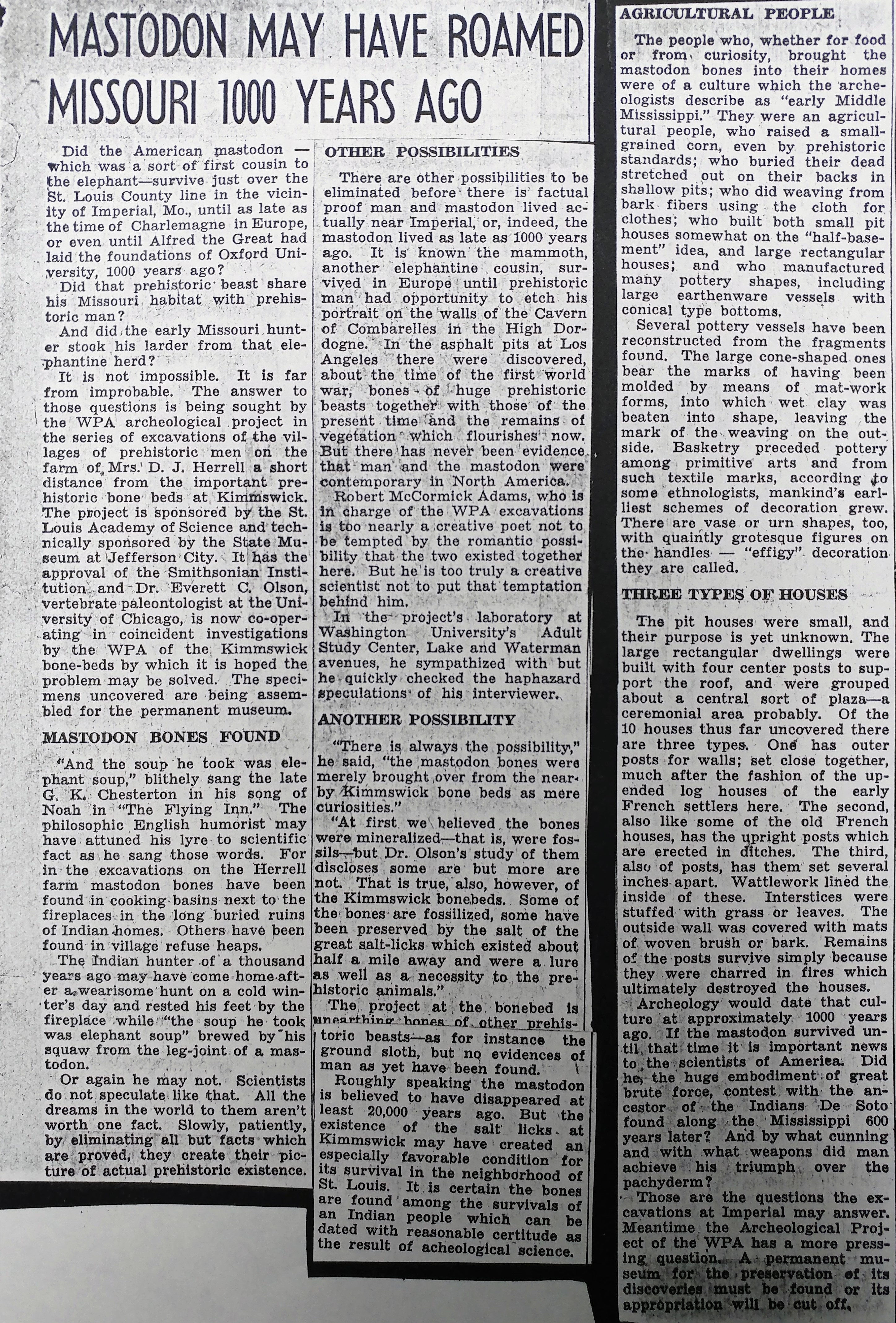

Mastodon May Have Roamed

Missouri 1000 Years Ago

Did the American mastodon – which was a sort of first cousin to the elephant – survive just over the St. Louis County line in the vicinity of Imperial, Mo., until as late as the time of Charlemagne in Europe, or even until Alfred the Great had laid the foundations of Oxford University, 1000 years ago?

Did that prehistoric beast share his Missouri habitat with prehistoric man?

And did the early Missouri hunter stock his larder from that elephantine herd?

It is not impossible. It is far from improbable. The answer to those questions is being sought by the WPA archeological project in the series of excavations of the villages of prehistoric men on the farm of Mrs. D. J. Herrell a short distance from the important prehistoric bone beds at Kimmswick. The project is sponsored by the St. Louis Academy of Science and technically sponsored by the State Museum at Jefferson City. It has the approval of the Smithsonian Institution and Dr. Everett C. Olson, vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Chicago, is now co-operating in coincident investigations by the WPA of the Kimmswick bone-beds by which it is hoped the problem may be solved. The specimens uncovered are being assembled for the permanent museum.

MASTODON BONES FOUND

“And the soup he took was elephant soup,” blithely sang the late G. K. Chesterton in his song of Noah in “The Flying Inn.” The philosophic English humorist may have attuned his lyre to scientific fact as he sang those words. For in the excavations on the Herrell farm mastodon bones have been found in cooking basins next to the fireplaces in the long buried ruins of Indian homes. Others have been found in village refuse heaps.

The Indian hunter of a thousand years ago may have come home after a wearisome hunt on a cold winter’s day and rested his feet by the fireplace while “the soup he took was elephant soup” brewed by his squaw from the leg-joint of a mastodon.

Or again, he may not. Scientists do not speculate like that. All the dreams in the world to them aren’t worth one fact. Slowly, patiently, by eliminating all but facts which are proved, they create their picture of actual historic existence.

OTHER POSSIBILITIES

There are other possibilities to be eliminated before there is factual proof man and mastodon lived actually near Imperial, or indeed, the mastodon lived as late as 1000 years ago. It is known the mammoth, anther elephantine cousin, survived in Europe until prehistoric man had opportunity to etch his portrait on the walls of the Cavern of Combarelles in the High Dordogne. In the asphalt pits at Los Angeles there were discovered about the time of the first world war, bones of huge prehistoric beasts together with those of the present time and the remains of vegetation which flourishes now. But there has never been evidence that man and the mastodon were contemporary in North America.

Robert McCormick Adams, who is in charge of the WPA excavations is too nearly a creative poet not to be tempted by the romantic possibility that the two existed together here. But he is too truly a creative scientist not to put that temptation behind him.

In the project’s laboratory at Washington University’s Adult Study Center, Lake and Waterman avenues, he sympathized with but he quickly checked the haphazard speculations of his interviewer.

ANOTHER POSSIBILITY

“There is always the possibility,” he said, “the mastodon bones were merely brought over from nearby Kimmswick bone beds as mere curiosities.”

“At first we believed the bones were mineralized – that is, were fossils – but Dr. Olson’s study of them discloses some are but more are not. That is true, also, however, of the Kimmswick bonebeds. Some of the bones are fossilized, some have been preserved by the salt of the great salt-licks which existed about half a mile away and were a lure as well as a necessity to the prehistoric animals.”

The project at the bonebed is unearthing bones of other prehistoric beasts – as for instance the ground sloth, but no evidences of man as yet have been found.

Roughly speaking the mastodon is believed to have disappeared at least 20,000 years ago. But the existence of the salt licks at Kimmswick may have created an especially favorable condition for its survival in the neighborhood of St. Louis. It is certain the bones are found among the survivals of an Indian people which can be dated with reasonable certitude as the result of archeological science.

AGRICULTURAL PEOPLE

The people who, whether for food or from curiosity, brought the mastodon bones into their homes were of a culture which the archeologists describe as “early Middle Mississippi.” They were an agricultural people, who raised a small-grained corn, even by prehistoric standards; who buried their dead stretched out on their backs in shallow pits; who did weaving from bark fibers using the cloth for clothes; who built both small pit houses somewhat on the “half-basement” idea, and large rectangular houses; and who manufactured many pottery shapes, including large earthenware vessels with conical type bottoms.

Several pottery vessels have been reconstructed from the fragments found. The large cone-shaped ones bear the marks of having been molded by means of mat-work forms, into which wet clay was beaten into shape, leaving the mark of the weaving on the outside. Basketry preceded pottery among primitive arts and from such textile marks, according to some ethnologists, mankind’s earliest schemes of decoration grew. There are vase or urn shapes, too, with quaintly grotesque figures on the handles - “effigy” decoration they are called.

THREE TYPES OF HOUSES

The pit houses were small, and their purpose is yet unknown. The large rectangular dwellings were built with four center posts to support the roof, and were grouped about a central sort of plaza – a ceremonial area probably. Of the 10 houses thus far uncovered there are three types. One has outer posts for walls; set close together, much after the fashion of the upended log houses of the early French settlers here. The second, also like some of the old French houses, has the upright posts which are erected in ditches. The third, also of posts, has them set several inches apart. Wattlework lined the inside of these. Interstices were stuffed with grass or leaves. The outside wall was covered with mats of woven brush or bark. Remains of the posts survive simply because they were charred in fires which ultimately destroyed the houses.

Archeology would date that culture at approximately 1000 years ago. If the mastodon survived until that time it is important news to the scientists of America. Did he, the huge embodiment of great brute force, contest with the ancestors of the Indians De Soto found along the Mississippi 600 years later? And by what cunning and with what weapons did man achieve his triumph over the pachyderm?

Those are the questions the excavations at Imperial may answer. Meantime the Archeological Project of the WPA has a more pressing question. A permanent museum for the preservation of its discoveries must be found or its appropriations will be cut off.

©2019 Jefferson County Missouri Heritage & Historical Society